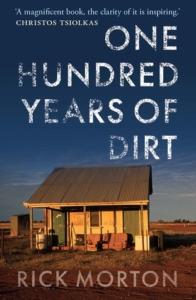

ONE HUNDRED YEAS OF DIRT | RICK MORTON | 2018 non-fiction

Memoir has never been one of my favourite reads: either unbearably sad, or too self-indulgent or fiercely vindictive. Rick Morton’s memoir has none of these attributes. Yes, there’s sadness, and in places it’s harrowing but his narrative is peppered with conclusive research into the recurring themes of his life; examinations that give deep insights into poverty, inequality and mental illness. It is these intervals of research that elevate this book to a unique understanding of what it means to be poor, and also a breather from the harsh realities of his young life. The research gives the book firm foundations and an opportunity to exhale before the next chapter.

Rick was born into a landed but dysfunctional heritage, perpetuated by a father who, even years later, cannot acknowledge he is a father in any meaningful way. Rick’s family of mother Deb, older brother Toby and younger sister Lauryn are cast out into poverty in the town of Boonah in Queensland. Rick knows he’s different to his brother and father, both men’s men who scorn education for rough riding and rough manners, violence, alcohol and drugs. It’s Rick’s mother Deb who is his salvation during an incredibly difficult childhood, teen years and into his maturity.

This book is an ode to his mother: to her self-sacrifice, understanding, level-headedness, and kindness under all manner of awful adversities. He reveals his own difficulties with always being the outsider, the one with gaps in his cultural and everyday knowledge, being gay and suffering from debilitating anxiety.

Sadly, he writes that there are people who have no idea of what true poverty means, that they suggest the poor give up cigarettes and alcohol or gambling. He counters that in his experience his mother did none of those things, to which one response was, “I don’t believe you.” Yes, there are people so devoid of any semblance of understanding of true poverty that makes a cup of hot chocolate at a café a luxury and highlight of the week. He cites author Tim Winton who says there are those who see poverty and discern only a failure of character. Rick talks about the “silkiness” of privilege, “their bubbles so perfect they cannot feel the gravel underneath”.

Rick Morton is an award-winning journalist. His narrative is at times melancholy but never morbid, the writing is succinct but not once self-serving and at times achingly funny and yes, sad. But it’s not sad without hope, he has achieved success, and his insights into the lives of the poor are eye-opening for those who haven’t lived it. His major theme is that you can take the boy out of poverty but you cannot take poverty out of the boy. He laments the possibility that once poor, always poor, that scrimping on necessities is a way of life for those who live hand to mouth, a way that is difficult to shrug off and stays in the persona long after the poverty has devolved. But the over-riding theme is that in his relationship with his mother there is never any poverty of spirit or love. Theirs is a joyous relationship.

If you can read this book without having experienced any of Rick’s traumas, fears or angst you have a truly blessed life. This book is inspirational without ever trying to be. And that is its gift to the reader.